How MƒA helped Rami Abdelghafar foster a more authentic learning experience for his students right in their own backyard.

Rami Abdelghafar remembers a particular moment early in his time as an MƒA Master Teacher, during a 2019 workshop called “Designing Science Curriculum to Liberate Students in the Consortium.” As he listened to his fellow teachers talk about building projects around issues that directly impact their students and their communities, he reflected on his own biology curriculum at Bronx Collaborative High School. How, Abdelghafar wondered, could he more fully engage his students’ identities and passions and foster a more authentic learning process?

As a first-generation Egyptian American born and raised in Harlem, he knew the importance of identity in the learning process. “Growing up…a lot of the time what I did in school was nothing related to who I am as a person, or even the community as a whole,” Abdelghafar says. “OK, we’re learning biology, but we’re focused on this park in Kansas or somewhere else across the world.”

Inspired by his MƒA colleagues, Abdelghafar realized that he could create a real-world project-based learning experience for his students — right in their own backyard. “Van Cortlandt Park is directly across the street from the school, but the students didn’t even know it existed,” Abdelghafar says. “They thought it was just a cute little park, because we only see the trees from our school building.”

"I actually have imposter syndrome as a teacher, but every teacher in MƒA truly respects you and brings the best out of you. Finally I’m feeling like I can be who I am, and truly be myself."

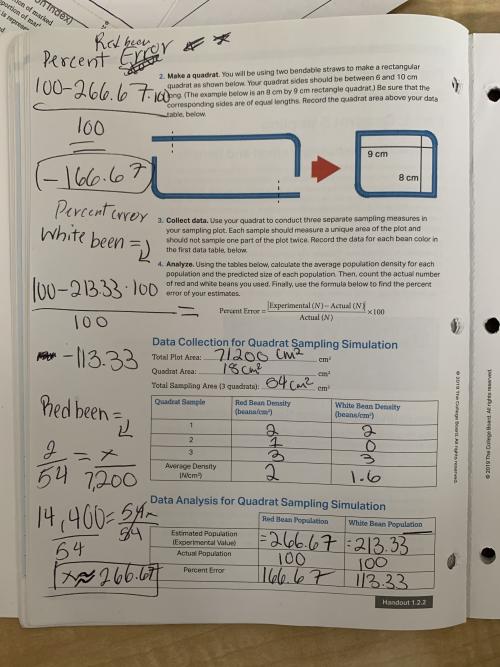

In the months following that curriculum workshop, Abdelghafar and his students began exploring Van Cortlandt Park, which at more than 1,000 acres is the city’s third-largest park. While the students collected data on different plant and animal species, many of their efforts involved Prunus Serotina (or black cherry), which was relatively easy to observe and track the change in population over time. With Abdelghafar’s guidance, students used the quadrat method, a common tool for ecologists seeking to measure biodiversity. Using tools found on Google Earth, they marked off squares (or quadrats) in the park, each measuring 20 by 20 meters or so, and counted how many cherry trees they could find inside each square. To measure human impact, they compared quadrats further into the park to those found on its edge, which would typically see more human interaction.

Then came the spring of 2020 and the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed swiftly by the closure of all New York City schools and a city-wide lockdown. Like many teachers, Abdelghafar struggled to see how he could continue to engage his students through virtual learning. He shared his concerns with other MƒA teachers, and the conversation led to another breakthrough: His students could build on their scientific skills by investigating how the COVID lockdown, and the relative lack of human interaction, was impacting Van Cortlandt Park.

When Abdelghafar brought the idea to the students, “they were captivated,” he says. They headed back to the park, and started collecting more data, which they compared to the numbers they had collected pre-pandemic. But the students’ work went beyond data collection. “We’re also thinking about the complex systems in place — the food web, the flow of energy in the environment,” Abdelghafar says.

On one trip, he noticed a student filming herself in the park for a video to share on TikTok. “I said to her, ‘this is great, but how do we make it something that is evidence-based?’” Abdelghafar recalls. The student went on to collect an image of a coyote print, cherry blossoms, and other species in the park, along with screenshots of the Google Earth quadrat sampling map, and include them in a video shared with her 100,000 followers. Abdelghafar was inspired by this example of the “butterfly effect,” or the idea that a small, localized change in a complex system can lead to bigger changes elsewhere.

“All her viewers were having this intellectual debate in the TikTok comments,” Abdelghafar says. “Some were like, ‘Maybe humans are not needed after all in nature,’ or ‘Maybe we really do mess things up.’ That was the beauty of it.”

After another student told Abdelghafar about the Van Cortlandt Parks Alliance, he contacted that organization to discuss how the students’ work could help improve the park’s biodiversity. Later, his students read and analyzed various city policies having to do with the park, and wrote their own impact reports based on their findings. “Knowing that they’re already empowered, I gave them the tools to advocate for themselves, on their behalf, and as a community,” he says.

Among his colleagues, Abdelghafar also saw the effects of his experiment multiply. “Our school community now focuses on…what students are expected to know and complete using authentic instruction in all subject areas,” he says. “We focus on student identity by showcasing their skills, talent, and creativity, and what they want to do, not what the teacher told them to do.”

In addition to the curriculum workshop, Abdelghafar has been inspired by other MƒA programs, most recently a course on Javascript and computer engineering that he’s planning on using to develop the Van Cortlandt Park project even further. “I’m hoping that next year students will learn to code, so they can actually create websites where we can check out and use the data they’ve collected,” he says.

One opportunity in particular — to create a workshop with another MƒA teacher on best practices to prepare students for AP Biology — tested the limits of what Abdelghafar felt himself to be capable of. But with the support of his fellow educators, he came through the experience feeling more confident than ever. “I actually have imposter syndrome as a teacher, but every teacher in MƒA truly respects you and brings the best out of you,” Abdelghafar says. “Finally I’m feeling like I can be who I am, and truly be myself.”

Photo credit: NYC Parks