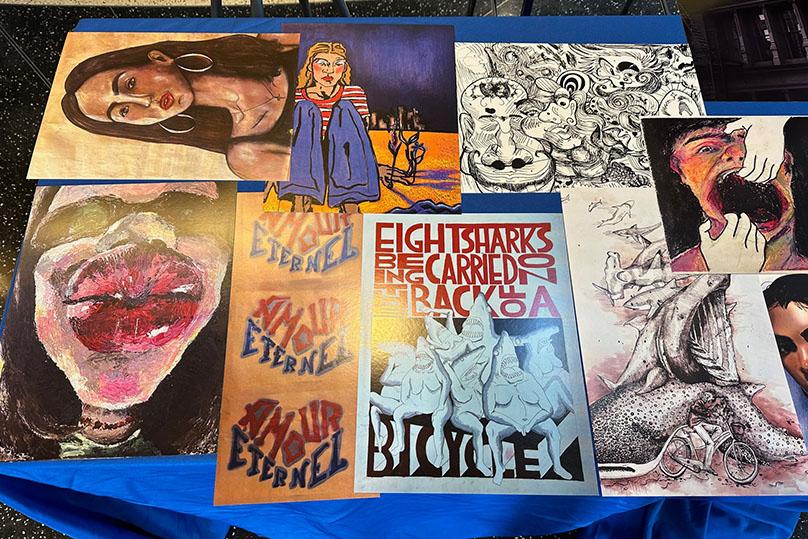

How Daniel Madden discovered why arts is an essential part of the STEM curriculum at MƒA.

In the spring of 2022, MƒA Master Teacher Daniel Madden took the MƒA mini-course “Light and Art: Full STEAM Ahead,” taught by Dr. Mark Rosin, a practicing scientist and assistant professor of mathematics at the Pratt Institute of Art and Design. While Madden had experimented with bringing art into his science classroom before, the mini-course was the first time he saw the full potential of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math) and got concrete resources he could use to engage his students.

“Oftentimes I found myself using art as a medium to express concepts in science, but not as much investigating how deeply entwined they are,” Madden says. “But as I got to see what these artists are actually doing, it opened my eyes more to things that could be done.” He especially appreciated how the mini-course presented examples of how art and science intersected, such as animators developing cutting-edge mathematics techniques to simulate the movement of water.

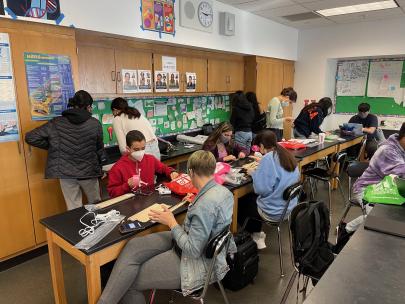

Madden wasted no time in bringing the resources shared in the mini-course back to his physics classroom at Frank Sinatra School of the Arts High School. One of them, known as the “Mantis Shrimp Game,” gave him the opportunity to explain how color vision works through metamerisms, or objects of different colors that appear to be the same color under certain lighting conditions.

“I built these little LED cubicles with old paper boxes, and I had a remote control that I could use to change the color of all the LED cubicles at the same time,” Madden says. “I ushered all the students out of the classroom and put the blocks under the lighting conditions. When I turned the light on, you could see that under blue light your red blocks are going to appear a similar color to other blocks, depending on the colors they reflect to our photoreceptors.”

The exercise had an immediate impact on his students, giving them new insight into the concepts of color vision, reflection and absorption, and piquing their interest in learning more about the properties and behavior of light. “It was an 'aha' kind of moment,” Madden says. “Some students in the class were actually pretty well versed in [how the human eye works], and there was an entry point there for discussions.”

Not only was the game a hit — it also helped Madden give his students a new perspective on accessibility in the classroom. One student in Madden’s class had significant hearing and vision issues, and he noticed that fellow students sometimes had a hard time connecting with her. He made a point to talk to his class about how the Mantis Shrimp Game was designed to highlight how all tasks are not created equally, and certain differently abled people may struggle to complete tasks due to factors beyond their control.

Equipped with up to 16 different types of photoreceptor cells in their eyes, mantis shrimp see the world in a range of colors compared with humans, who have just three types of these cells. “In essence, you’re playing a game that you may have a disadvantage at to some degree,” Madden says. “This can give us an idea of what it might be like to enter a game or some other situation in which you're being assessed, and you don't have the ability to play that game because you weren't necessarily given those instruments. These moments are critical points at which we understand that others are different from us, but that's okay, and we can still make these connections.”

The experience helped Madden himself become more aware of how to create a truly accessible learning environment. “After going through that with the students, and specifically with that one student, I just knew that I had to differentiate more,” he says. “It really comes down to how you design the actual assessments that you’re going to be giving, and the delivery of the course material in and of itself, so we can all take different takeaways from it.”

Now at Midwood High School, Madden plans to keep bringing STEAM into his physics classroom there, including the Mantis Shrimp Game. “I’m a big believer that arts is an essential part of the STEM curriculum for everybody, not just for artists,” he says.

Beyond the STEAM mini-course, Madden relies on MƒA for fueling his need for continued learning and professional development, as well as giving him access to resources and support from other passionate educators. “I wish every teacher had access to these kinds of resources,” he says. “It really helps to reshape the way you think about education, and the way that students see teachers and teachers see students.”

In a world where STEAM professions can feel exclusionary, Madden believes doors need to open to allow new minds and perspectives in. He says "differentiation may be the best tool to broaden scientific literacy."