How MƒA helps Laura Ralph explore the natural world and amplify her students' scientific wonder.

In the summer of 2021, MƒA Master Teacher Laura Ralph spent an exhilarating 10 days in the Galapagos Islands during a course for educators run by the nonprofit Ecology Project International (EPI). Amid tagging giant sea turtles, eradicating invasive species in the Santa Cruz highlands, and cleaning up microplastics on beaches, she thought about how she could bring what she was learning back to her students at River East Elementary School in East Harlem.

“Part of what we did there was the field work, and part was — how are we going to bring this back to our classrooms?” Ralph says of the Galapagos trip, for which she received a grant from MƒA that enabled her to participate. “What is it that we’re getting out of this experience that we can make sure our kids are also getting?”

As a longtime teacher of elementary school science, Ralph is well aware of the research showing that spending time exploring nature helps students learn better. But for her and many fellow teachers, that’s often difficult to achieve due to classroom and school restrictions. In addition to furthering her own learning, Ralph’s experience in the Galapagos gave her both inspiration and a tangible resource: a lesson framework that she could adapt to local ecology and conservation work in the New York area.

“In a big urban environment like New York, you’re not often thinking of the animals and plants,” Ralph says. “A big piece of it was thinking about what our kids have in their own backyard that they may or may not be aware of, and how we can bring that back in.”

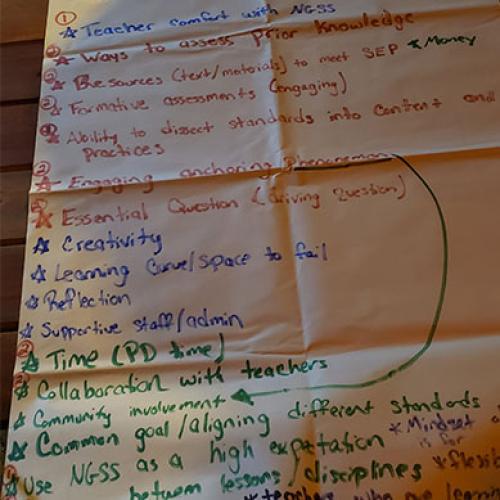

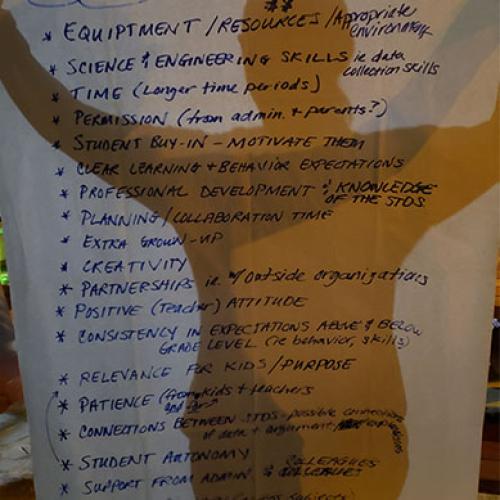

"What do we need to design lessons based on the Next Generation Science Standards?" Standards set the expectations for what students should know and be able to do.

"What do we need to implement the Next Generation Science Standards in field studies?" Ralph and others worked on creating a framework for integrating NGSS skills into the classroom.

Upon her return, Ralph set to work creating hands-on nature-based learning opportunities for her K-5 students. Having previously participated in an MƒA workshop about oyster restoration, she reached out to its facilitators, who put her in touch with the Billion Oyster Project (BOP). The nonprofit organization aims to restore 1 billion of the natural filter feeders to New York Harbor by 2035.

In partnership with BOP, Ralph brought two oyster research tanks into her classroom, each stocked with juvenile oysters, known as spat. In the weeks and months to come, Ralph’s older students tested the water quality in the tank and collected data on the growing oysters, using calipers to take measurements. Younger students read books like How the Oysters Saved the Bay by Jeff Dombek, and were able to connect what they read with the real-life bivalves in their classroom.

Whatever their grade, all of Ralph’s students got the chance to observe and interact with the oysters and other inhabitants of the tanks, including amphipods, clam worms, sea squirts, barnacles, hydroids, and tunicates. “Some kids are hesitant at first, like, wait, I’m not sure if I want to touch that,” Ralph says. “Some kids are just ready to be all hands on and stick their hands in the tanks and do all sorts of things. [With] the kids that are more hesitant, it's nice to see their growth over the year.”

Thanks to a partnership with the Billion Oyster Project, Ralph brought two oyster research tanks into her classroom, each stocked with juvenile oysters, known as spat.

Ralph’s students tested tank water quality and collected data on the growing oysters. They read books that helped them connect ideas to real-life bivalves in their classroom.

As her colleagues in other departments grew interested in Ralph's project, its impact reverberated beyond her own classroom. An art teacher incorporated ecology lessons into her class by having the students work with the ceramic-like material called ostra, made partially from oyster shells. Social studies teachers connected the study of oysters with their unit on the history of the Lenape Native Americans and organized field trips to look at oyster shell remnants in Inwood Hill Park. “The teachers were excited to see how engaged the students were,” Ralph says.

Going forward, Ralph is committed to continue working with the oysters, and even collaborated with BOP to gain a permit for a research station closer to her school. “We’ll be able to go right down there and have our own cage that we can monitor,” she says. “It’ll be a nice connection to have [oysters] both in the classroom and right down the street, so students can see where they actually live and where they come from.”

Keeping students connected with the natural world around them is important to her for various reasons. “Education is a big piece,” she admits. “Oysters are also a keystone species, and such a big part of New York. It’s important for kids to make those connections.”

In addition to funding for exciting opportunities like the Galapagos trip, Ralph relies on MƒA for support, inspiration, and continued learning. “There are no restrictions on what we can learn,” she says. “MƒA puts a lot of trust in [its] teachers. I think when you have that trust, you rise to it and do more.”

The highlands of Santa Cruz are home to endangered subspecies of Galapagos tortoises. Ralph weighed and measured tortoises and gathered GPS data to help scientists better understand survival and mortality rate of those like Dora (seen above).