How MƒA Master Teacher Sylvia Gayatinea creates connections between nuclear chemistry, history and ethics for her students.

Over the past several years, Master Teacher Sylvia Gayatinea has taken two MƒA courses focused on nuclear weapons taught by Dr. Ivana Hughes, a senior lecturer in chemistry at Columbia University. She also attended a lecture Hughes delivered about her work with Columbia’s K=1 Project, which researches the legacy of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands in the 1940s and ’50s.

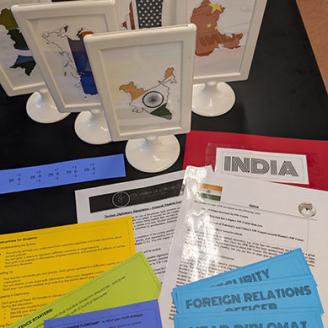

At one point, Hughes introduced a nuclear diplomacy simulation, which challenged students to step into the roles of scientists, diplomats and world leaders to tackle tough questions about nuclear energy, weapons and global policies. Gayatinea saw immediately how the exercise could help her illuminate some of the more abstract concepts she explores with her own students at the Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology.

“I have to teach nuclear chemistry, but it’s very dry,” she says. “It's not like I can bring nuclear radioactive isotopes in the classroom to make it interesting.”

When she used the nuclear diplomacy simulation with her students, Gayatinea saw its impact instantly. Teachers in her school’s history department helped support her efforts by ensuring the students were well grounded in the history of nuclear weapons development in World War II by the time their nuclear chemistry unit began. “It’s amazing to see students trying to balance scientific facts with political realities,” she says. "They’re realizing how chemistry connects with ethics and history in a way they hadn’t considered before.”

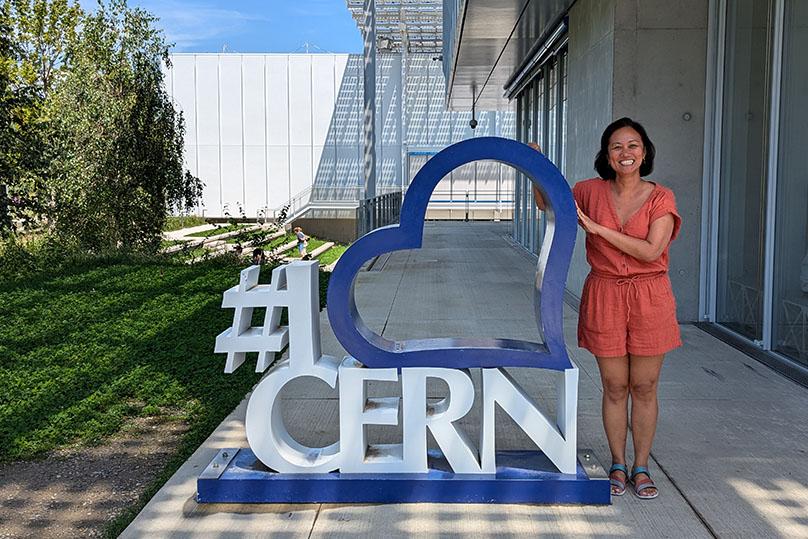

Scences from Gayatinea's solo trip to CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research.

CERN offers PD programs for teachers to learn about particle physics and related fields.

This newly expansive perspective led Gayatinea to a life-changing experience in the summer of 2024, when she made a solo trip to CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Located on the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva, the intergovernmental organization operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Her exposure to Hughes’ work had inspired Gayatinea to learn more about quantum mechanics, a topic she had always wanted to explore but never had the chance to dive into. “I wanted to learn something different, and maybe I could bring something back to my students,” she recalls. “I got more than I anticipated.”

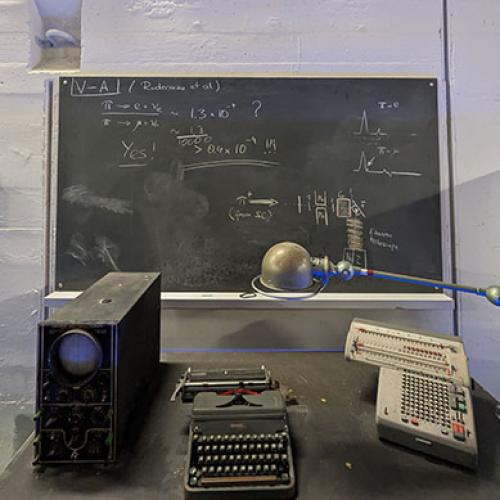

At the Science Gateway, a museum that CERN scientists use to share their work with the public, Gayatinea participated in immersive exhibits, laboratory workshops, lectures and a guided tour of the facilities. She also took full advantage of access to the physicist assigned to her group, who readily answered her many questions about topics such as the Higgs boson, the fundamental particle of the Higgs field, which is responsible for giving other particles their mass. First proposed in 1964, its existence was confirmed in a CERN laboratory in 2012.

The intergovernmental organization operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world.

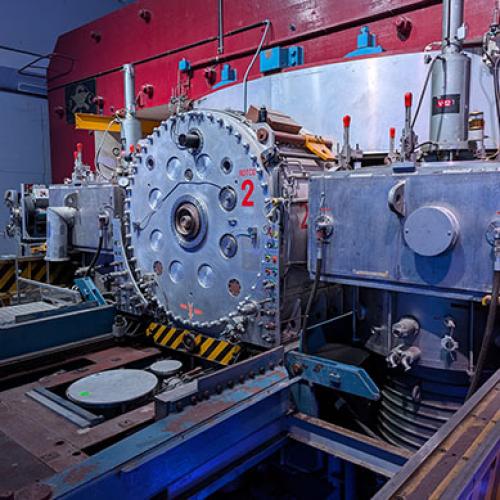

CERN is home to some of the largest and most complex scientific instruments.

Back home, Gayatinea created a simple classroom activity based on what she had learned at CERN. Students broke into groups, and she gave each group a gift-wrapped box and asked how they could know what was inside without peeking, using things like sound, feel and logic.

“While it was a simple exercise, it led to meaningful conversations about how we make the invisible visible in science,” she says. “For the first time, no student asked ‘If atoms are so tiny, how do we know they exist?’ This was a breakthrough in my class.” She hopes to schedule a virtual talk by the CERN physicist she met to further expose her students to the lab’s groundbreaking work.

Physicists and engineers at CERN study the basic constituents of matter – fundamental particles.

At CERN, Gayatinea participated in immersive exhibits, laboratory workshops, lectures and a facilities tour.

Gayatinea has never shied away from tackling new challenges as an educator — the previous spring, she chaperoned a trip to Japan — but after the trip to CERN she was inspired to create a professional bucket list of future goals. “I realized how important it is to have goals to keep me excited and motivated in my work,” she says. “It helps me focus on what’s important.”

This summer, thanks to an impact grant from MƒA, Gayatinea will head to Bali as a volunteer teacher. She has also used grant money to start an art and science club at her school, a passion project that involves taking students to the Natural History Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and other locations around New York City where they can connect art and science.

In an effort to share the benefits of her own experience, Gayatinea hopes to facilitate a course through MƒA about how her fellow teachers can create their own professional bucket list. “We’re always looking for ways to stay inspired and keep growing in our careers,” she says. “This will be a great way to connect, share goals and find new ways to keep the passion for teaching alive.”

“It’s amazing to see students trying to balance scientific facts with political realities. They’re realizing how chemistry connects with ethics and history in a way they hadn’t considered before.”

On her trip to Japan, Gayatinea appreciated the opportunities to connect culture and science. She established genuine connections with her students that strengthened their community and brought them closer together.