MƒA Master Teacher Nasriah Morrison uses her MƒA fellowship to empower students of color to see themselves as mathematicians and scientists.

Type “famous mathematicians” into a search bar and Google returns 14 images across the screen. Thirteen of the images are men, and one is a woman. All of them are white. Three are Greeks, and the rest are European. Hidden from view is Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, the great Persian scholar whose work was central to the development of algebra. (You can find him, but you have to scroll).

For many students of color, their experience in STEM subjects is similar to this Google search. They see few examples of prominent mathematicians and scientists who look like them. Textbooks, class examples, and the media often portray successful mathematicians and scientists as white men. Around 90 percent of public school STEM teachers in the U.S. are white, and students of color often go from early grades all the way through high school without ever having a teacher of color.

MƒA Master Teacher Nasriah Morrison uses her MƒA fellowship to tackle this important problem. She co-facilitates a Professional Learning Team with MƒA Master Teacher Jae Berlin called Mathematicians and Scientists Who Look Like Me: Teaching Racially Expansive Histories. The group develops tools and strategies that help teachers challenge stereotypes and integrate historical and contemporary mathematicians and scientists of color into their teaching.

“Math is a subject in which we don’t really teach the history of what students are learning, let alone the stories of the people who have been effectively erased from our curriculum,” Morrison said. “By diving into these stories, as well as those of mathematics practitioners from our community, we’ve started challenging students to rethink what it means to be an expert in STEM.”

The group explores existing resources and thinks about how they can best be put to use in the classroom. The materials include books, websites, and articles that examine the accomplishments of mathematicians and scientists of color in context. Morrison believes contemporary examples are particularly important, and she sometimes goes to great lengths to find them.

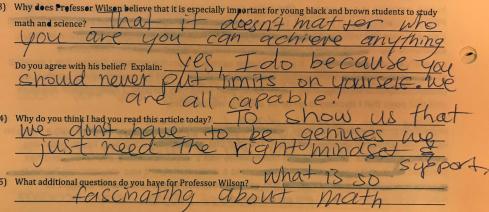

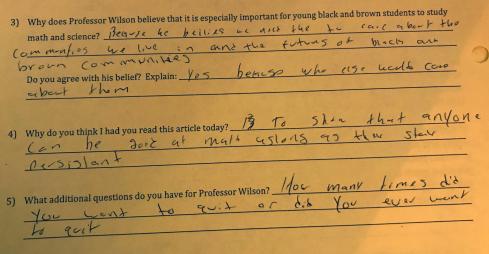

Morrison used an MƒA Impact Grant, for example, to attend a workshop at the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute in Berkeley, California. There she interacted with mathematicians of color from around the U.S., including Robin Wilson, an associate professor of mathematics and statistics from California State Polytechnic University. Wilson directed her to an online anthology of black mathematicians known as “Mathematicians of the African Diaspora.” Morrison shared stories from the anthology, including Wilson’s own, with her students. Students posed their own questions for Wilson, with some even requesting to meet him in person. “It’s something our students don’t see a lot of examples of in their daily lives. It was a great way to connect their own experiences as students to what it means to be a mathematician, and specifically one of color.”

Due to Morrison and her colleagues’ efforts, classrooms across the city benefit from innovative ways to highlight STEM professionals of color as a routine part of instruction. Fellow MƒA Master Teachers James Cleveland and Sarah Van Etten-Thomas began running “Mathematician Mondays,” a time set aside to look at mathematicians of color and the problem-solving skills used in their work. MƒA Master Teacher Tracy Tran started implementing “Skype a Scientist” in her classroom, allowing students to interact with real scientists in real time. MƒA Master Teacher Sarah Gribbin used research from current scientists working on Flint, Michigan’s water supply to kickstart a project where students investigated lead contamination in New York City’s water system.

Morrison works to make sure that these ideas for improving instruction spread beyond her group at MƒA. Together, her and Berlin released a “Racially Expansive STEM Histories” resource document that consists of websites, databases, and content-centered lesson ideas that educators across the city can access to help build a deeper understanding of how students’ identities contribute to and expand their masteries of STEM content.

Supplementing curriculum is hard work, but Morrison says it pays off when all students, and particularly students of color, change the way they think about the nature of math and science, as well as who does the work. “People perceive math as something that’s already developed, something that’s static and passed down to them instead of something that others who look like them are creating and discovering,” Morrison said. “This contributes to students of color feeling like they don’t have an active role in the process. As teachers, we need to do everything in our power to change that.”

"Math is a subject in which we don’t really teach the history of what students are learning, let alone the stories of the people who have been effectively erased from our curriculum. By diving into these stories, as well as those of mathematics practitioners from our community, we’ve started challenging students to rethink what it means to be an expert in STEM."