How MƒA helps Francisco Pérez Martínez engage his students by immersing them in the natural resources of their city.

Master Teacher Francisco Pérez Martínez, Paco, remembers the evening he spent in May 2019 listening to bird calls in Madison Square Park as part of the MƒA minicourse “Population Biology by Birding the Concrete Jungle.” A native of Spain who had been teaching in New York for more than a decade by that point, Paco was bowled over by the unexpected natural diversity of his adopted city. “In the end, through listening and watching, we identified around 12 species,” Paco recalls. “It was amazing.”

He particularly appreciated how the course’s facilitator talked about how easy it was for students to gather their own field data from bird populations. This brought home to Paco that he didn’t have to be an expert to lead such efforts himself. With new confidence, he resolved to try it with his eighth-grade science students at P.S./I.S. 173 in Washington Heights. While the arrival of the pandemic delayed his first attempt, he remained inspired, even taking his own young daughter on a bird walk through Fort Tryon and Inwood Hill Park.

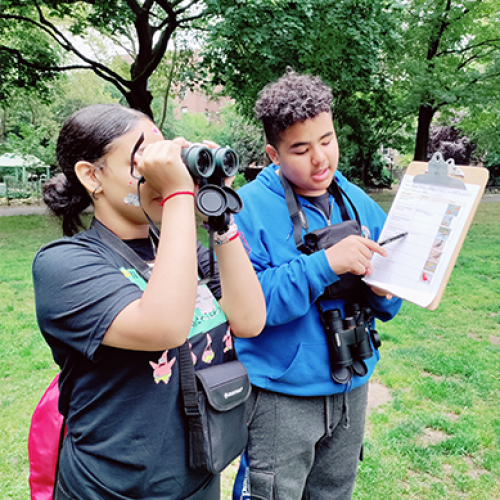

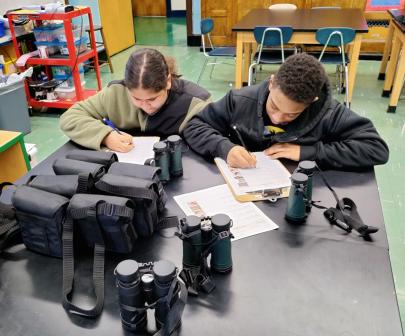

Finally, with restrictions on in-person learning starting to ease during the 2021–22 school year, Paco took his students out in the park near the school for their first bird watching excursion. “They worked in groups identifying bird species and counting individuals,” he says. “We calculated averages and published our data on eBird, the app developed by Cornell University.”

Paco saw an immediate impact on his students in both their level of engagement and their performance on assessments after the unit. “They learned how to describe populations, communities and ecosystems,” he says. Getting outdoors helped their motivation as well: “It makes them more engaged, because they're learning about the city where they live.”

Paco takes his students out to local parks for bird watching excursions. They work in groups identifying species, counting individual birds, and publishing data on eBird.

Students learn how to describe populations, communities and ecosystems. Paco often sees a positive impact on their level of engagement, motivation, and performance.

Building on his success, Paco was inspired by another MƒA mini-course to immerse his students further into the natural environment of their city. That course, “Introduction to NYC’s Water Story,” was facilitated by the director of education for the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Paco was impressed by the breadth and depth of resources the department had made available to teach students, not only about water but about air quality, noise pollution, invasive species and the impact of climate change.

At the time, Paco saw a clear need at his school to educate students about the water system. In the wake of the pandemic, the students were refusing to drink from the water fountains, forcing the principal to bring in shipments of Poland Spring water and plastic cups. While in New York City “we have the best water system in the world,” Paco says, “all the kids were going [to the water dispenser], and when there were no plastic cups, it was like the end of the world.”

Along with one of his colleagues, Paco decided to adapt some of the DEP curriculum for their students. They chose several activities, including scavenger hunts that asked students to find facts about waste water treatment on the DEP website and helped them understand New York City’s watershed area, the 2,000-square mile area of land that collects and stores the city’s drinking water. “This kind of science is locally based, so kids are more interested because this is the water they’re drinking,” Paco says.

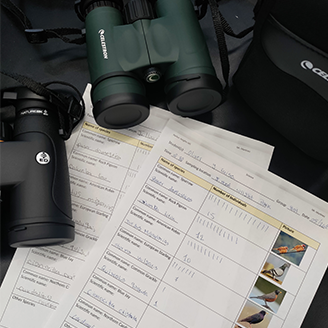

The reorganization of his school and departure of his colleague has forced Paco to put further exploration of the water-focused curriculum on hold, but he hopes to resume and expand on it in the future. Meanwhile, he has made birdwatching a key part of his general science curriculum. During the 2022–23 school year, he used MƒA funds to purchase multiple sets of binoculars, which made identification of bird species easier. On the most recent trip, the group was able to spot four different species in the nearby park — starlings, sparrows, American robins and pigeons — and compare the numbers of each one by creating graphs. “Sometimes the most important thing is the kids having fun while they're learning,” Paco adds.

Being part of MƒA has also helped Paco develop different aspects of his teaching, including class management and ensuring he’s asking the right questions of his students. Drawing on his experience teaching newcomers to the United States, Paco recently co-facilitated a workshop on science for multilingual language learners. “We're 12 teachers that are facing the same problems in the classroom, and we're trying to share how we’re dealing with those problems and trying to overcome them,” he says.

Paco also appreciates the ongoing support and camaraderie he gains while learning from and with his fellow teachers. “Every time you get [to MƒA], you feel valued,” he says. “It keeps you going really, because sometimes it's not that easy.”

How might teachers use birding to engage students in inquiry-based learning? Paco says if they can identify a pigeon from a starling, they’re halfway to being able to do species counts and population studies.